The autonym of this group, Duay Muak Sa-aak, means “mountain slope.” The Tai Lue people in the area call them Doi, and the Shan call them Loi. Both these names mean “mountain.” Many young people in this group no longer use the name Muak Sa-aak, but refer to themselves as Doi. The elderly, though, still remember their tribal name and are glad whenever they hear it. Until 2017, Muak Sa-aak was considered a variety of Tai Loi, but it is now known to be a separate language. In Myanmar, few people have ever heard of the Muak Sa-aak, and they have never appeared on government lists of the country’s ethnic groups.

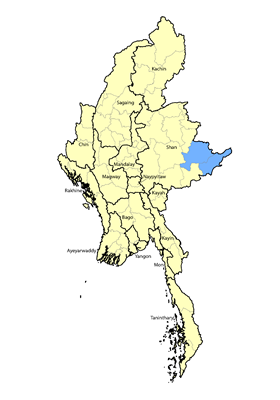

Location: Numbering approximately 4,800 people in Myanmar, the little-known Muak Sa-aak tribe are distributed in villages along the Chinese border in Shan State. Their largest village is home to 620 people and is located a stone’s throw from China in Mongyang Township. For generations, people freely passed across the international border to visit relatives or to trade, but in 2020, China’s President Xi Jinping used the spread of Covid as an excuse to construct an electric barb-wired fence the entire 1,323-mile (2,129 km) length of Myanmar’s border with Yunnan Province. Movement has been severely restricted since that time. An additional 1,000 Muak Sa-aak people inhabit four villages on the Chinese side of the border in Yunnan Province. Other Muak Sa-aak are believed to live in northern Thailand, but they have struggled to preserve their language there and it may now be extinct.

Language: Muak Sa-aak, which has three tones, is one of several Angkuic languages spoken in this part of Shan State. These varieties fall within the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austro-Asiatic language family. Linguists have studied the language extensively and have shared their research in several papers.1 Muak Sa-aak, which enjoys widespread use among the people, is reportedly most closely related to Mok, but it shares only a 25% and 35% lexical similarity with the two Mon-Khmer languages of Parauk Wa and Blang, respectively. Regarding the relationship between Muak Sa-aak and Mok, one scholar says: “They are similar, but…there are significant differences in lexicon and phonology that require them to speak Shan with each other. They live in different areas of Shan State so do not regularly encounter each other, although culturally they are similar.”

Although little is known about the origins of the Muak Sa-aak, one theory says that large Mon-Khmer speaking groups, including the Wa, formerly lived in northern Thailand, where they were influenced by Buddhism. Later, “after the main body moved northward, various groups were left behind. These remnants, over many years of separation and isolation, developed different dialects which have resulted in new tribal subdivisions as seen today.”

Like other people groups in this region, the Muak Sa-aak live simple lives as they try to provide for their households by growing rice and vegetables. Most also raise chickens, while the more financially secure families own pigs and other livestock to supplement their diets and income.

Although all non-Christian Muak Sa-aak people today are Buddhists, in the past tribes in the area “propitiated the spirits by making chicken, pig, and buffalo sacrifices. Shamans and exorcists held a high position and were thought to be the only ones who could control malevolent spirits.” After being Buddhists for at least several hundred years, the Muak Sa-aak no longer sacrifice animals, although they may offer plates of food to the spirts.

Using the Roman orthography, the first book of the Bible was translated into the Muak Sa-aak language in 2017, and by late 2025, 19 New Testament books had been completed, suggesting that the New Testament will be published in the next few years. It is hoped the Scriptures will cause a breakthrough among the Muak Sa-aak, strengthening Christians and opening the hearts and minds of those who have yet to hear the Gospel.

Scripture Prayers for the Muak Sa-aak in Myanmar (Burma).

| Profile Source: Asia Harvest |